5 ways a neuropsychology translator can help you

In my last post, I mentioned how the inner workings of neuropsychology are sometimes difficult to grasp, even for other psychologists not directly working in this discipline.

As a neuropsychologist, I understand that, for precisely this reason, there's a certain uneasiness at allowing “outsiders” to translate specialized neuropsychology texts. You might find yourself in doubt and thinking: Is the translator going to be able to understand what is being measured? Are they going to be able to convey the instructions correctly in another language and get the importance of doing so? And what about visualizing how every subtest, scale, score and norm, and every stimulus sheet, scoring key, and manual tie together as a whole in the way my team and I intended? Do they really understand what's at stake here?

But as the need for collaboration with international teams or a test publisher occurs, or as the opportunity to use the instrument as a clinical outcome assessment (COA) as part of a clinical trial with international sites arises, translating neuropsychology content professionally is something that might come sooner or later, as there's too much at stake to try the DIY approach.

Here I follow on from my previous post about neuropsychology translation, this time focusing on the figure of the translator specializing in neuropsychology as a partner who can help you in several ways.

- 5 ways a translator specializing in neuropsychology can help you

- They know neuropsychology assessment

- They understand the objective of the assessment and the adaptation process

- They understand the key roles in an assessment context

- They realize the issues and challenges when testing the target population

- They get what's at stake

- Conclusion

5 ways a translator specializing in neuropsychology can help you

1. They know neuropsychology assessment

Neuropsychology tests use a great variety of complex activities as testing conditions. These include (but go way beyond) ticking A, B, C, or D. They can have the test taker doing puzzles, playing a musical instrument, playing cards, drawing weird shapes, reading colorful words, etc. Additionally, a number of well-known cognitive testing paradigms (e.g., go-no-go, n-back tasks) have served as the basis for further assessment methods.

A neuropsychology translator understands not only the tools but also the specific challenges related to the assessment setting. They know that clinicians are always finding the balance between building rapport with the patient and following the standardized process. For this reason, they have to be able to translate instructions and materials that keep administration variability and errors to a minimum.

The translator specializing in neuropsychology must understand the implicit “rules” of this specific context, the most-used materials, stimuli, and tasks, and have some fundamentals of psychometrics and knowledge of the rules of item writing.

2. They understand the objective of the assessment and the adaptation process

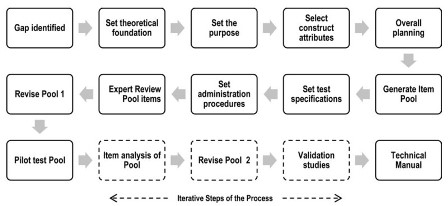

Scale development process: integrative approach (Source: The Steps of Scale Development and Standardization Process)

They know a test shouldn't just be translated word for word. What is important is that the original meaning is conveyed and the items assess a construct. The translator needs to understand this process and, ideally, be familiar with the measured constructs at some level.

They know they are involved in just one of the many steps in a much bigger process comprising a large cross-disciplinary team. They know that approaches are different depending on whether the objectives are diagnostic/interventional or clinical research. If a translator understands the process of test development and adaptation, they won't introduce changes haphazardly: There's an implicit “trust” in what the team of psychometricians and subject matter experts wanted to convey within each item and the test as a whole.

With this awareness and respect for the adaptation process, the specialized translator in this field also sees the need to appropriately record every decision each step of the way and appreciates the importance of doing so for regulatory compliance/traceability.

3. They understand the key roles in an assessment context

Translation is not just about the explicit words or the constructs. There is also the wider context. Everything that's going to be translated needs to be analyzed through the lens of the target culture.

For example, a neuropsychology translator who is also knowledgeable about the target culture and language might explain to you that referring to “psychometrists” doesn't make sense, as it's not a role that exists in the target culture (which is the case in most Spanish-speaking countries). Or they might explain that mentioning doctoral degrees (PhD, PsyD) as essential criteria is not entirely correct, due to different country requirements on the pathways to becoming a test user/administrator.

4. They realize the issues and challenges when testing the target population

Most tests are developed from a Western or developed-country perspective. This poses a problem for test takers from other cultures, who might end up with confusing instructions or less-than-optimal testing situations that influence how they interact with the test administrator (or rater) and the test itself, potentially affecting their performance.

Even though, on the surface, an English-to-Spanish adaptation of a test might require less drastic changes (e.g., we use the same alphabet), there are many other cultural aspects that might impact test validity. As the Colombian neuropsychologist Alfredo Ardila has discussed, there are many cultural values that are implicit in a neuropsychological assessment setting, and these can impact cognitive performance: one-to-one relationship, background authority, best performance, isolated environment, special type of communication, speed, internal or subjective issues, use of specific testing elements, and testing strategies.

One example of how a seemingly simple test has to be adapted for Spanish speakers is the COWAT. In English, this test uses the letters F, A, and S to measure verbal fluency, but it has been adapted to use P, M, and other letters considered more suitable for Spanish as the performance was not consistent across languages.

Another factor to bear in mind is that Spanish is spoken in many countries that have their own distinctive cultures, even if they share the same language. Take the Boston test, for example. This is a traditional naming test that uses images, one of which depicts asparagus. This could be used in Spain, where this is a well-known plant, but not in Colombia, where it wouldn't be recognized by most people (believe me, I've seen this test being applied to Colombian patients without adaptation). Thus, a test for Colombia and one for Spain might have differences in the stimuli that are presented or even in the way instructions are given.

5. They get what's at stake

Validity is, as the Standards mention, “the most fundamental consideration in developing tests and evaluating tests.” For this reason, one of the aims of test developers and test users is to decrease the impact of bias that can threaten the validity for specific contexts/uses.

Just like the example I gave in my previous post, some of these errors on administration manuals and scoring sheets can cause confusion, which can result in test administrators guessing the meaning. This takes away from the reproducibility and consistency needed in a standardized procedure.

Some tests don't have practice items and don't allow administrators to repeat instructions, so errors in the instructions given to the test taker can make them fail the trial. Unclear wording can also have an impact on motivation and effort, which again can affect performance.

In general, all of these errors can impact measurement validity, introduce variance, and give rise to many other undesirable effects that will make the collected cognitive data less useful. And, if the aims of the neuropsychology assessment are diagnostic or interventional, to provide appropriate supports for someone's mental health, rehabilitation possibilities, education, or work life, it's crucial that the translation is fit for purpose.

Conclusion

Just like any other specialized field, highly specialized content is better left to highly specialized linguists (if you're wondering about why and what to translate in neuropsychology, take a look at my last post).

Neuropsychology tests are highly refined measurement tools, and just like it's better to think twice about who to commission for the translation of a manual for laboratory or diagnostic equipment, the same is true for neuropsychology instruments.

There aren't many neuropsychologists who are also translators, but this might not be as important as having the right experience, education, and access to resources to deliver a good translation (I've written about this at length in my posts about Psychology translation as a specialism and Qualified psychology translators).

If you want a neuropsychologist who is also a translator for your English-to-Spanish language needs, someone who is a language specialist with first-hand experience of administering these complex tools, be sure to contact me and let's work together to reach your goals.

is a psychologist and English to Spanish translator. She specializes in the fields of psychology, healthcare and medicine, and education. In this blog, she writes about everything she knows or has learned that could be useful or of interest to you!